Digging into a Deadly Winter Storm with Cathie Pelletier

A Q&A with the best-selling Maine author about her new book, “Northeaster,” about the Blizzard of 1952.

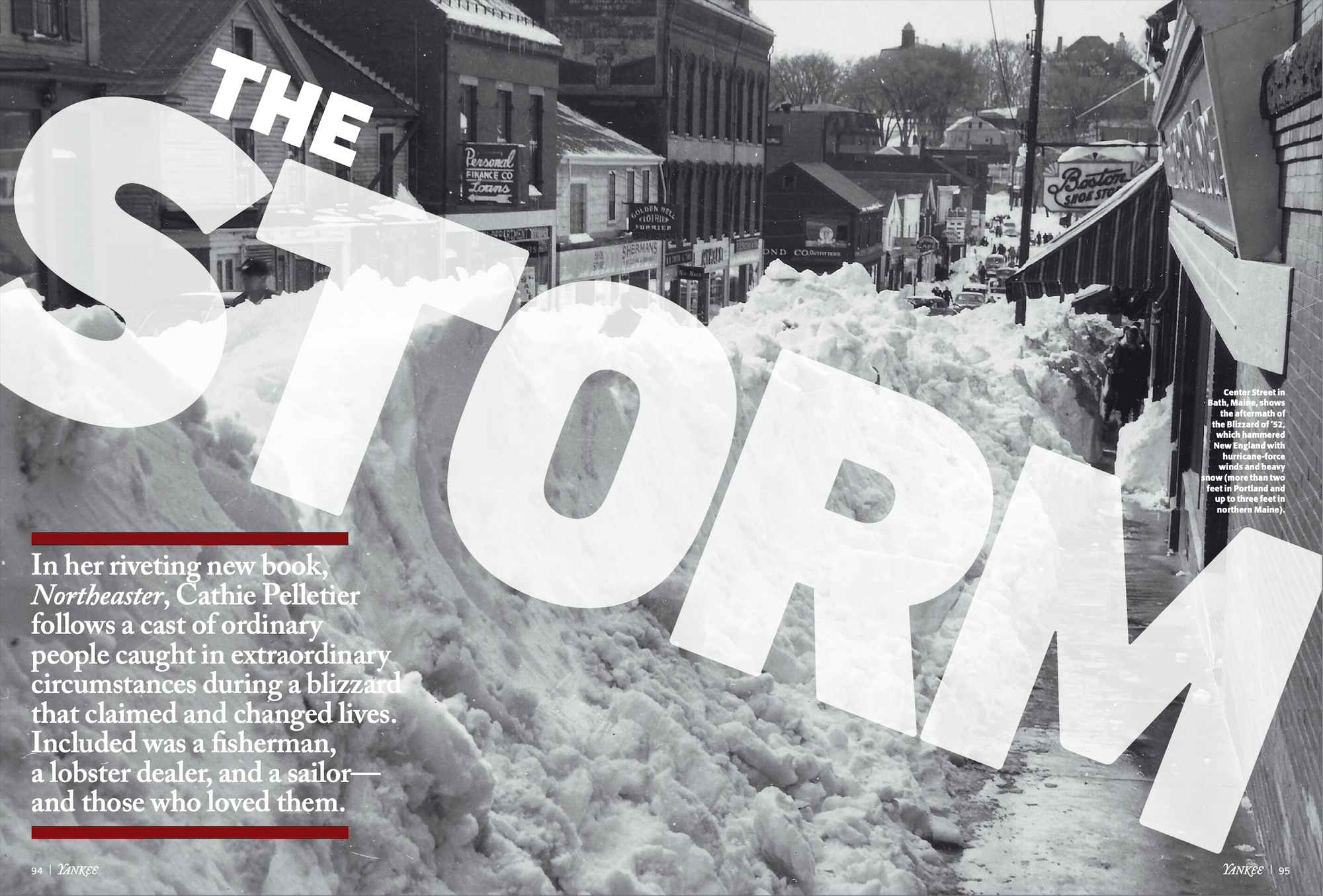

Just as a fierce winter storm hit Buffalo, New York, in December 2022 — claiming nearly 40 lives, including people who were buried in cars beneath feet of snow — Yankee editor Mel Allen spoke with writer Cathie Pelletier by phone at her home in Allagash, Maine, about her new nonfiction book Northeaster: A Story of Courage and Survival in the Blizzard of 1952.

Northeaster follows the stories of nine real-life people, as well as focuses on a turnpike rest stop that sheltered hundreds during the storm. The book excerpt that appeared in the January/February 2023 issue of Yankee features Maine lobsterman Harland Davis; lobster wholesaler Jimmy Haigh of Portsmouth, New Hampshire; and Paul Delaney, a sailor stationed in Winter Harbor, Maine, who became trapped in his car beneath 10 feet of snow after sliding off the road.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Cathie, the storm you write about happened the year before you were born. There have been many storms since 1952, yet you devoted years of your life to learning about something that happened long ago. How did it start?

A: It was 2005 and I was living deep in a Quebec forest in the Eastern Townships. It was snowing, so I Googled “snowstorms.” Old photos came up for Bath, Maine’s community page on Facebook. One was of a pregnant woman being hauled to a hospital by toboggan. I had often thought of attempting a nonfiction book. So I emailed libraries in Bangor and Portland for newspaper clippings about that 1952 storm. I soon had a fat packet of material. I scribbled “Snowstorm 1952” on it. When I moved back to Allagash in 2009, it ended up in a box in my basement.

I wrote more novels. Then I wrote a book proposal based on Einstein’s theory of relativity being proved by a 1919 eclipse. Knowing zero about physics, I ordered tons of books and stared at them until my eyes bled before I found a co-author in Jim Gates, a theoretical physicist and National Medal of Science recipient. I treasure our friendship, but co-writing that book for over three years almost killed me [Proving Einstein Right: The Daring Expeditions That Changed How We Look at the Universe]. I hoped it would satisfy my curiosity about a world outside fiction. But when I came off the road in 2019, from my last signing event with Gates, I put my suitcase down and said to my husband, “There’s an envelope in the basement with ‘Snowstorm 1952’ written on it.” A half hour later he emerged with it in his hands. At least the Einstein book taught me fortitude.

Q: And that was your mission then?

A: Yes. And then, I know how incapacitating snow can be. I remember as a child how it would pile up almost to our second-story windows.

Q: How does a fiction writer enter the nonfiction world?

A: I was curious about nonfiction for years. I was impressed with Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, and later John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil and Sebastian Junger’s The Perfect Storm. I was surprised to read recently that Mailer’s book won the Pulitzer for fiction. And that facts in Berendt’s book, listed as a novel, were changed to keep the story flowing. Junger also says he relied on facts as much as possible, but occasionally turned to narrative nonfiction. I wasn’t sure I could find enough facts to write about a 70-year-old storm and unsung characters. But that fall of 2019, I started Northeaster. To bring the main characters alive I had to invent. What I learned from that amazed me. After almost 40 years of writing fiction, I’m obsessed with the truth. That’s because a fiction writer creates a world built on facts, our truth. We’re in charge of everything about that world, the geography, the people. A reader might not like our world. They might close the covers on it and put it down. But fiction is all true. This new genre felt like cheating.

When I wrote the nonfiction book about Einstein, if I couldn’t find a fact, I wouldn’t put it on the page. That was a result of my many years as a fiction writer. If I didn’t know what color shirt Einstein had on the day his wife and sons left Zurich on the train, I refused to imagine a color. This is different from a fiction writer. If we write, “It was raining when John got up and put on a blue shirt,” then it’s a fact. It’s the world we created, and we also control the weather and what clothes a character has in the closet. But Einstein was a real man, living a real life. If Mileva had written in a letter that, “Albert was wearing a green shirt the day I left Zurich with our boys,” then I would have dressed him in a green shirt.

Thus, when I came up against this 1952 storm, all the main people were long gone. And then, they were regular folks, not Einstein or famous astronomers. Those guys left letters and papers in archives around the world, now accessible from my Allagash computer. I even found some grandchildren still alive who were pleased to talk about their once-famous grandfathers and share memories and photos. As a result, Proving Einstein Right is the only book that delves into the personal lives of those astronomers. So how could I get to know those obscure Maine people? How could I give them dialogue? And then, one story has an ocean setting. I was born and raised on this St. John riverbank. That’s like a chihuahua compared to the ocean being an Old English sheepdog. I knew I had to find descendants willing to talk to me.

Q: How did it actually begin, the research and writing?

A: It started with Tom finding the old packet in the basement. Then Covid hit so I had an excuse not to leave Allagash as I wrote. In a way, imagining all those towns as they were in 1952 was probably better than visiting them 70 years later. I found community pages on Facebook for some towns. And more newspaper clippings. The Internet had grown mightily in the past 15 years. Folks on those pages love to remember the past. The Bath community page was very active. My pregnant woman came from there, so I was delighted to see that her son had posted about her. I emailed him and his sister. When I asked about the 1952 storm, more family members and friends appeared for other principal characters. I started pestering archives in Maine, historical societies, and so on.

The greatest gift I found on that Bath community page was Kerry E. Nelson, the woman I call “my indentured assistant.” She has worked for years in history for Bath and other places and is a whiz at finding things I hate to look for: census reports, birth and death certificates. Kerry is also nosy as I am. If I asked her to find news about a train wreck, she’d send it. She’d also send a fascinating item that neither of us had any business reading. We went down dozens of rabbit holes, fascinated with old murders, heiresses, or dead sailors washing ashore in 1898. I was six months into the book when Kerry and I met. We still have not met in person, as with most of these people who helped me with the book. That Kerry swears as much as I do was a bonus.

When I bogged down, I’d asked myself: “Why don’t you write another novel? Why take on stuff you know nothing about?” Well, we teach ourselves in this way, I suppose. When I began the ocean story, I was so naïve that one of my questions to a long-retired fishermen was “Did you just throw the lobsters into the boat?” He explained to me that no, there were lobster crates in 1952. Can you imagine? I hadn’t even thought of a crate. That’s because you can throw trout into the belly of a canoe. I’d ask people, “What’s the difference between a pier, a dock, and a wharf?” Once I was done with the ocean, I started bothering retired railroad men like Ron Knowles. “Was it steam or diesel in 1952? How did the plow train work? How long before a train going 35 mph can stop?” Physics, oceans, and trains are among my short suits. Looking back from this perspective, I would never attempt it.

Q: Do you keep in touch with the people who told you the stories you used in the book?

A: I’m in close touch and always refer to it as “our book.” I sent them files so they could see the stages as a book is readied for publication. They are the reason I was able to write it. Mary Tardif Wirta, who lives in Connecticut, estimates I sent around a thousand questions in the two years I asked about her mother, Hazel. “Did your mother dance? Did she wear an apron? Did she have favorite expressions? Could you see the Penobscot from your house?” The son of Harland Davis, the lobsterman I write about, came to Allagash so we could meet. Sue Godley and I are in close touch. She now lives in Georgia and is the daughter of one of my fishermen. James Haigh’s daughter lives in Pennsylvania. And Paul Delaney’s daughter is in New Jersey. Paul was the young sailor in the book.

Q: The 1952 storm affected thousands of people. You made the decision to frame it around a small subset of people — some of whom survived, some of whom did not. How did you know who to focus on?

A: I chose stories that stood out in those 1952 newspapers, such as the two ice fishermen trapped on a lake. I knew six people had died in Maine. That tends to get the most ink, of course. But I also needed characters who survived. I saved a lot of stories I didn’t use. I checked the other day, and my research for Northeaster was 1,765 files stored in 112 folders. But the Einstein book had three times that. Tell me again why I didn’t become a lawyer? I have a whole new respect for historians and nonfiction writers.

Q: When you immerse yourself in something it probably becomes part of you. How did that happen for you in this case?

A: As sometimes happens with fictional characters, I dreamed of Harland Davis. In one dream we were in a library. Maybe Monhegan since I had written about their library that day, and it’s the island where Harland went for lobsters. He was dressed in a coat he had on in a photo his son sent me. He said, “There are papers here you can find.” I have no idea what that meant. I put my head against his chest and he held me the way a brother might. I must have hit a wall working that day, thus the dream. Of course, Kerry believes in these messages “from beyond.” I say it’s my subconscious mind at work. This is another reason Kerry and I were a good pair. I felt such sadness for Harland and his wife, Alice. And Barbi Haigh, who was 9 years old. She told me heart-breaking things, such as when her mother hit her head against the refrigerator saying, “Jimmy, Jimmy, Jimmy.” Most novelists know how characters can infiltrate their dreams.

Q: How did you recreate the sailor’s experience of being buried in the snow for days?

A: I talked to Paul Delaney’s wife in 2005, when I first thought of writing about the storm. He had died a year earlier. But she heard his story many times. She said, “I wrote down everything Paul said.” When I came to write the book 15 years later, she had also died. Her daughter searched but couldn’t find her mother’s writing. So I read articles about people trapped in cars. And I used logic. What would you do if you’re a guy and need to urinate? What would being trapped hours beneath snow feel like? I also read papers on sensory deprivation.

Q: Did everyone understand that sometimes you had to create what likely was said and thought?

A: They all gave me full permission. I sent them paragraphs as I wrote, and then the finished manuscript. Because they trusted me, I worried about getting it right.

Q: There is an impression of Mainers that they are reticent, not apt to open up. How did they react to you wanting to know about their lives and their memories?

A: Two of the daughters grew up outside Maine. Some may have been reticent in the beginning. But they grew to trust me as we went along. But I worried, knowing what it’s like when words go into cement. I’d say, “Read what I just wrote about your mother. Are you sure this sounds like her?” I especially hounded Bill Wilson about the excerpt you chose for this magazine. His life is buried at the end of the book, in my epilogue where I update the reader. But for this issue, it was right out there. He and his wife, Sandy, reassured me more than once that it was fine. I felt very protective of them all. They became like family.

Q: The book is done. It’s being published now in January. What is motivating you to keep searching for what happened to people in the storm?

A: I was lucky when an archivist at the National Archives in D.C. found the 1952 Coast Guard report filed by Westin Gamage, a minor character. On that old report are the names of the coast guardsmen who were stationed at Burnt Island in 1952. Kerry and I searched the 50 states trying to find them. With Westin dead, they’re the last eyewitnesses to that day. I got trapped on the phone too often with people whose fathers had the same name, and were even in the coastguard, but not the right men. One or more might still be alive, in their late 80s or early 90s. They would have the most definitive answer for Harland’s son and Jimmy’s daughter as to the rescue attempt.

Q: The book is not just about a storm. It is also about a way of life that people once knew.

A: That’s how I felt while writing it. I miss that world. Often I’d play the hit songs of 1952 as I worked. I read up on 1952 movies and dress styles. Cars became like minor characters. I was born a year later, but that whole decade resonates. I’m now working on a screenplay of my first novel for director Doug Liman and producer Gabrielle Tana. It has a 1957 setting, so I’m still back there. What’s the name of the Mickey Gilley song? “Lost in the 50s Tonight.”

Q: This book shows us one storm, but I came away feeling it also was about all the storms without warnings that hit all of us in our lives.

A: Yes. Any disaster, big or little, when ordinary lives are disrupted, can be the stuff novels are built on. Everyone’s story is important in their family’s history. Just being alive is a brave thing to do. So when a calamity appears it magnifies everything.

Mel Allen

Mel Allen is the fifth editor of Yankee Magazine since its beginning in 1935. His first byline in Yankee appeared in 1977 and he joined the staff in 1979 as a senior editor. Eventually he became executive editor and in the summer of 2006 became editor. During his career he has edited and written for every section of the magazine, including home, food, and travel, while his pursuit of long form story telling has always been vital to his mission as well. He has raced a sled dog team, crawled into the dens of black bears, fished with the legendary Ted Williams, profiled astronaut Alan Shephard, and stood beneath a battleship before it was launched. He also once helped author Stephen King round up his pigs for market, but that story is for another day. Mel taught fourth grade in Maine for three years and believes that his education as a writer began when he had to hold the attention of 29 children through months of Maine winters. He learned you had to grab their attention and hold it. After 12 years teaching magazine writing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, he now teaches in the MFA creative nonfiction program at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Like all editors, his greatest joy is finding new talent and bringing their work to light.

More by Mel Allen