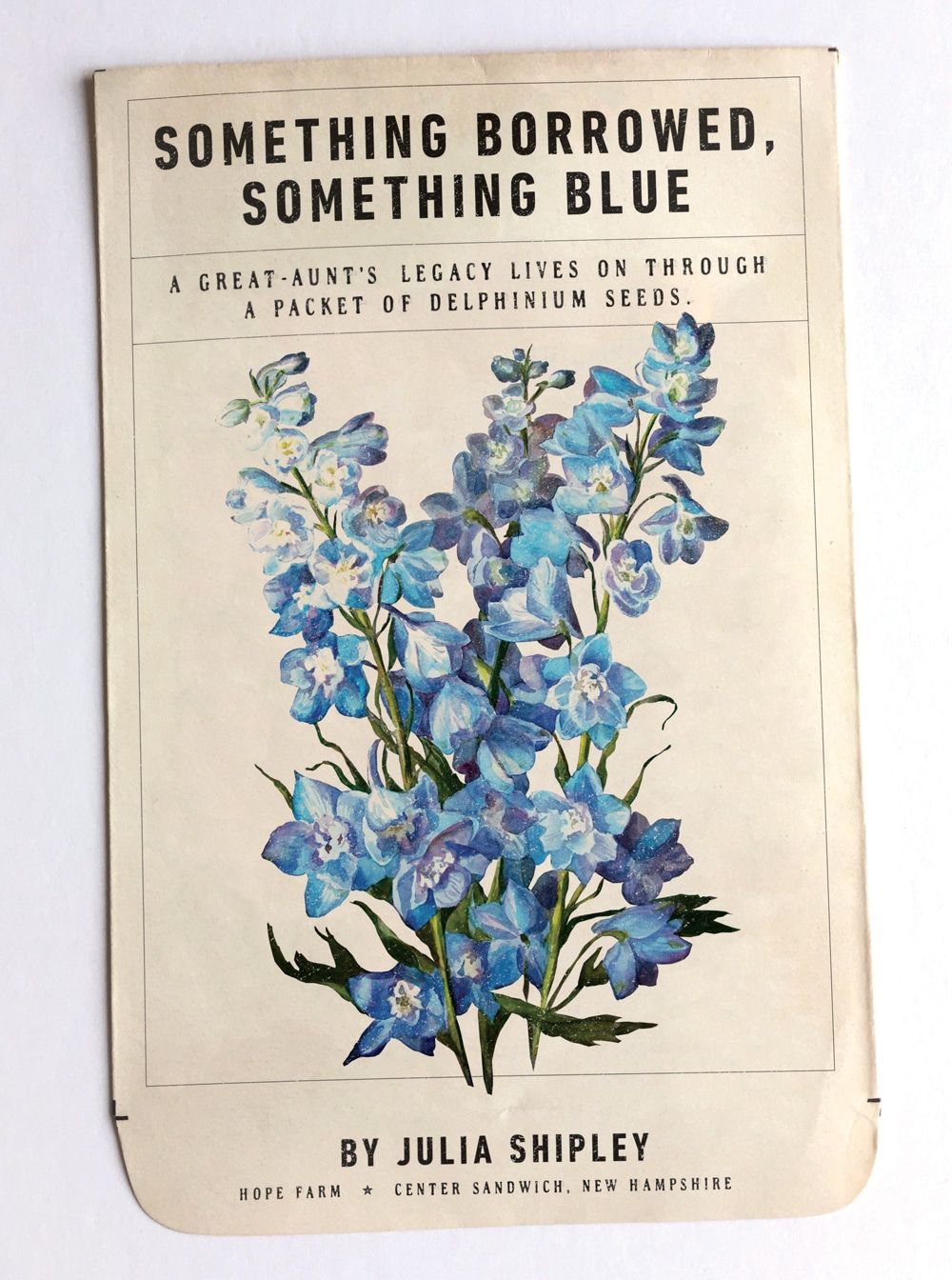

Something Borrowed, Something Blue

A great Aunt’s legacy lives on through a packet of delphinium seeds.

The first delphiniums I ever saw: A man arrived at the door bearing two tremendous spokes of blue. He looked so gallant and so silly at the same time, outdone by his preposterous bouquet—their stems were the length of a car antenna. Soaring from his fist, they poked the doorframe; I stared, dazzled, while my friends, the hosts, scrambled to find a vessel to accommodate his sapphire wands.

A handful of years later, my mom gave me an envelope of seeds marked “Delphiniums 1966.” She’d been cleaning out my great-aunt’s things and found them in a drawer. They must have been left over from Hope Farm in Center Sandwich, New Hampshire, the farm named after my great-aunt, and, well, the condition of positive anticipation.

Hope’s husband, Bill, was a courageous man with a feeble heart, a stockbroker whose doctor said (absurdly), “Try farming,” and so they did, replacing financial stock with livestock. They raised and milked Jerseys and delivered milk around town. They never had children of their own, but my mother spent her childhood summers helping Aunt Hope in the kitchen, and then, fetching the flat basket and clippers, heading out to the garden to cut bouquets.

By the time I was born, Aunt Hope and Uncle Bill had sold their herd. However, as I grew, my aspiration to raise animals and vegetables intensified, and when I’d visit or write to my great-aunt, she’d counsel me with all she knew.

In their envelope, her seeds look like coarsely ground coffee or flecks of tobacco, and I wish I could guess why—unlike so many other things from her life—they had persisted. Also, I wondered whether her delphiniums had been especially beautiful that year—the color of Uncle Bill’s eyes, or a first-prize ribbon at the Sandwich Fair? All through their blooming: U.S. planes started bombing Hanoi; race riots ignited in Cleveland; Bob Dylan crashed his motorcycle; workers broke ground for the World Trade Center.

In 1966, my mom was at college and my dad was working in New York City. I wasn’t even a gleam—my parents wouldn’t meet for two more years.

When I shake the envelope, it chatters with potential: ch, ch, ch.

In 2002, the summer my great-aunt died, I was working at a perennial farm in Vermont for a man who could propagate anything, even lady’s slippers. I showed him the packet over my lunch break. “Could you germinate them?” I asked. “Do you think they might take?”

He looked doubtful. “Mmm, probably not. But I’ll try.”

Suddenly my envelope seemed more like a purse of valuable coins. I had to choose: Should I invest them with the propagator, to potentially see a return in the form of blooming things? I knew that if each seed grew, there’d be 68 plants, producing a congregation of blue spires. However, if I turned them over only to learn their potency had expired, then all I’d have is the empty envelope: “Delphiniums 1966.” Then, silly as it is to say, my great-aunt would really be gone.

So I held on to them. I brought them with me when I moved into a farmhouse and began raising my Jersey heifers. The seeds bided their time in a drawer while I planted a garden around a perennial bed that included some delphiniums from my old boss’s inventory.

Every June, those tremendous spokes shot up through the carrots and potatoes, and by mid-July they loomed, cerulean blue, over the zucchini and beets. Amid the low-lying vegetables they looked both gallant and silly. I began to anticipate their blooming, a season within a season.

One day during delphinium season, seven years into work on my own hope-driven farm, I met a man with eyes the same color as the flowers. Three years later, in that enchanted mini season, we eloped beside the garden in front of the people who had made us. I carried a fistful of blue stalks for my bouquet.

When my father, the pastor, asked if anyone knew of a reason why we shouldn’t be joined in marriage, there were so few of us to reply that the question seemed ridiculous. The garden was our congregation; the delphiniums, witnesses to our vows, swayed in what I think was an assent to proceed.

Recently, I was pawing through a box at the back of my mother’s closet. In it, I found some pictures from Hope Farm. There’s one of my great-aunt standing in the dooryard after a whopper of a snowstorm, holding her toddler-size cats, Poukie and Missy, one under each arm. There are pictures of her flower garden featuring her soaring delphiniums. I also found an envelope just like the one containing the flower seeds, only this one was marked “Given me by Mary Wright.” Inside, there’s a snippet of yellow lined paper bearing a handwritten passage:

Lord, help me to go to seed. The fruit I want to bear for you is not some big juicy accomplishment, but the subtle scattering of seeds of your love in many hearts. One seed planted in a heart, nourished and encouraged to grow, can eventually mature and go to seed, yielding a hundred loving kindnesses … help me to go to seed for you.

My Aunt Hope once admitted to me how she and Uncle Bill had desperately wanted to have children, but “it wasn’t meant to be.” She remembered her sole pregnancy ended soon after she and Uncle Bill went for a swim in a too-chilly swimming hole.

It’s been more than 50 years since she gathered the seeds from her garden and pocketed them for a girl who hadn’t been dreamed of yet. This envelope has come over the White Mountains, and across the Connecticut River. I shake the dark pellets into my hand and let each one drop into a cup of this soil. Either way, she continues to live with me.

Julia Shipley

Contributing editor Julia Shipley’s stories celebrate New Englanders’ enduring connection to place. Her long-form lyric essay, “Adam’s Mark,” was selected as one of the Boston Globes Best New England Books of 2014.

More by Julia Shipley