Magazine

Greenfield, MA: Scale Model Town in His Backyard

In 1962 Waine Morse decided to build a make-believe store beside his vegetable garden in Greenfield, MA, to house his burgeoning collection of Americana. He couldn’t stop. Excerpt from “’The Man Who Build a Town in His Backyard,” Yankee Magazine, December 1989. It didn’t start out to be like this, a whole village, a toy […]

In 1962 Waine Morse decided to build a make-believe store beside his vegetable garden in Greenfield, MA, to house his burgeoning collection of Americana. He couldn’t stop.

Excerpt from “’The Man Who Build a Town in His Backyard,” Yankee Magazine, December 1989.

It didn’t start out to be like this, a whole village, a toy town that he built, one enterprise at a time. Waine Morse doesn’t know what it started out to be. He remembers that germ of it, a trip that he and his wife, just then his bride, took to a general store behind the Yankee Pedlar inn and restaurant in Holyoke.

Both schoolteachers, they had been married only a couple of months when in February of 1962 they took a trip during school vacation. It was raining, not a great day for an excursion, but when he saw this place, filled as it was with nostalgic reminders of the decades before — the coffee grinder and the penny candy and the old lanterns and the big potbelly stove — it struck him that that was what he would like to have. A store, a place to put reminders of times past.

He was 28 at the time, and he and Margaret had their whole lives together ahead of them. He had already built a small house for them on land that had belonged to his mother since the 1920s. This was just outside of Greenfield, Massachusetts, where the Mohawk Trail begins to climb west. Though it was modest from the outside –shallow-roofed and single-story — the inside gradually accumulated such Victorian treats as paneled walls and parquet floors, velvet couches and ancestral portraits. “It evolved,” he says. That’s the way Waine Morse works.

He started on the store, weekends and nights, building it like an old Cape, and roofing it with slate, taking the design out of his head. When he wasn’t building, he was collecting. “The first thing I got was a coffee grinder for $16,” he says.

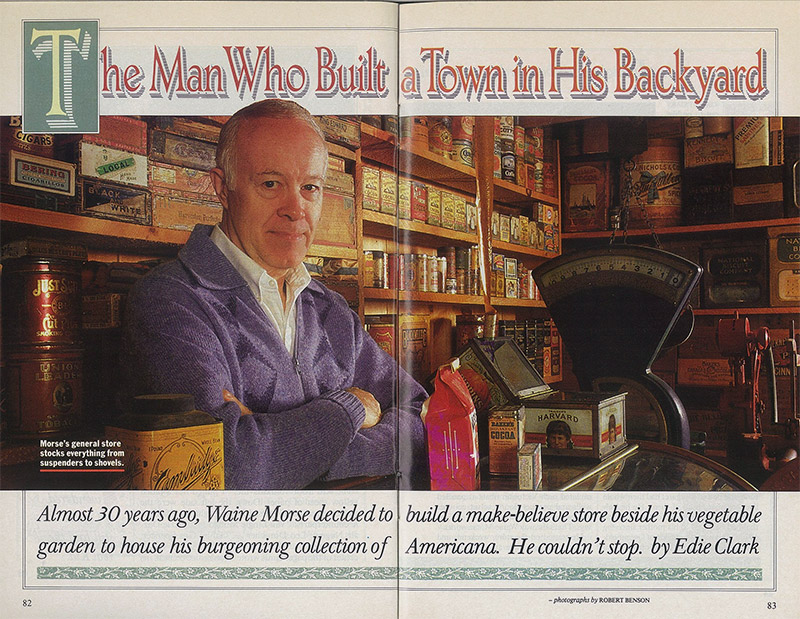

Amazing that he can recall, since now the store is stocked to its rafters, floor to ceiling, with washboards, boxes of crackers, butter churns, sacks of flour, coffee cans, biscuit boxes, cakes of Ivory soap, shovels, suspenders, crocks, apple peelers, racks of postcards –an endless inventory of stores past. It might justly be called the collection of a lifetime, except that there is so much else.

Waine Morse is 56 now, his gray hair is thinning, but there is still plenty of bounce in his step. He does not even call this a village. He has no name for this flourishing manifestation of the past, housed in what appears to be a group of sheds, sided in rough pine, the roofs like chicken barns.

It’s what’s inside that matters. Whatever it is, it now surrounds his house, hidden among trees and continuing up the steep hill above. There are weeds high around the foundations and the dirt paths are obscured by the overgrowth. Beside the vegetable garden, an old steam pumper is covered in plastic. Farther down is an old wooden milk wagon, badly in need of buttressing.

Next to the store is the pharmacy, which he built in 1969. “There was a drug store on the way to Sturbridge, in West Warren. I noticed one day that they were going out of business,” he says. He bought the counters and the glass cabinets, as well as the 14-foot-long wall that separated the pharmacist’s work area from his customers — a big, old-fashioned affair that includes mirrors framed by dark-stained wood pillars.

He took it down and brought it back to Greenfield, piece by piece. He reassembled it inside his new building. He worked alone — he did then and does now. From that old drug store and from others, and from items bought at flea markets and yard sales, he began to stock the shelves.

Like the general store, there is not a hairline left for expansion. Crammed into the cases and up on the shelves, Waine has lined up hundreds of packets of herbs (frostwort, blessed thistle, horehound, ignatia) and assortments of salves and medical assists — King’s Kidney Plaster, Grandpa’s Pine Tar Soap, Corn Cure, Tuttle’s Family Elixir, Carter’s Little Pills, Dr. Blue Jay Corn Plasters, Kantleek hot water bottles, Red Raven Splits of “Laxative Water.” There they are, their labels still bright, the wrappers still sealed, full to the top with the old remedies.

Waine Morse has never tried any of them. “I just like to come in here and look,” he says. In the windows sunlight shines through big blue and amber apothecary jars. Other jars and bottles crowd in, shoulder to shoulder.

The store is long since complete. There are two reasons for that. When he was gathering stock for these shelves, in the sixties and seventies, bottles and such could be had for not much. Now the prices are sky-high. “See those two cobalt bottles over there? They’d probably cost $75 apiece now, so hey, I’m done.” It’s not just the money. “I wouldn’t want to buy any more bottles. I would have to build another shelf, and once I hit the ceiling, that’s it.”

After the pharmacy he lost track of the sequence; the years seem to blur. “I’d have to look that up,” he says in answer to questions of when did he put in the doctor’s office and when did he reassemble the tinsmith’s shop. But in truth he doesn’t really have a place to look it up. He’s not absent-minded and heaven knows he is anything but disorganized. It’s just that there is so much. Beyond the pharmacy, there is a big building, more than 100 feet long, with add-ons like shops along a street. And several others, the doors to which Waine Morse opens like surprise packages, moving into the darkness and amid the smell of pine and sawdust until he finds the light, illuminating his creations.

In a comer he has the blacksmith shop, behind a glass wall made of old storm windows. The more-than-man-sized bellows, the anvil as big as a workbench, the collection of tongs on the side of the forge – all of it brought from different sources. Waine didn’t know too much about this kind of work. “For this I got a book that showed how it was done and so I said, ‘Okay, here we go,’ and I looked for one of this and one of that.”

When he read in the paper that Tony Trela, the last blacksmith in Greenfield, had died, he took note. “By the time I got down there, most everything was gone. The tools, that is. But I got what no one else wanted.

I got his chair, his gloves, his boots, and his two hats, one for summer and one for winter. I looked down at the floor. It was covered with metal filings and ashes and coal dust from the forge, old cigar butts and the parings from horses’ hooves.” Waine Morse’s eyes shine in recollection. “The man never swept. NO one else wanted it, but oh, it was beautiful, if you like such things.” Waine swept it up and brought it home. When the time is right, he will carpet the blacksmith’s shop with its majesty.

This is how he came by a lot of what he has. For the buildings, he kept his eye on the paper for old boards and materials. “I never actually took a building down, but I was standing right there while they were being taken down,” he says. And into the back of his father’s pickup would go the doors and the windows, the boards and the beams. Something like half of his buildings come from the old tom-down buildings and barns of Greenfield.

What else he gathered, of course, are the workings of his exhibits. Living as he did in the great industrialized mill valley, as the fifties turned to the sixties and the sixties to the seventies, one mill right after the other shut its doors in Greenfield, in Millers Falls, and most of all in Holyoke.

Most everyone else stood by and watched while this glum transition took hold. Waine Morse went in and got, taking apart the weighty machinery and trucking it back to Greenfield in the same borrowed pickup. “This would all have gone by, otherwise,” he says.

He is talking here not only about things such as the old cracker barrels of which nostalgists are so fond, but of an enormous treadle-operated lathe, a giant hand-cranked drill press, a belt-driven planer that weighs a full ton, an ancient table saw with a wooden bed and a blade reminiscent of scenes from the silent movies.

In the pattern-maker’s shop, bolted to the rafters, Waine has a rope winch that looks capable of reeling in the Queen Mary. Miles of hemp rope are wound to the spool. Waine says the entire unit weighs 1,800 pounds. He should know. “I put it up there piece by piece and it was a pain in the neck, but I bet there isn’t another one like it anywhere.” Probably not. He looks ground him, the tools silent but set like a stage, ready to come to life — all they need are the men and the women and the times past.

In rooms and in separate buildings, he leads me through his version of the past — a dry goods shop (“I’m going to hang curtains in here when the time comes”); the wheelwright’s shop (gently, he runs his fingertips across the spoked wooden wheel, set in its vise, half made); the ice cream parlor with the old marble fountain and soda dispensers (he walks in and straddles one of the stools, puts his elbows on the counter); the toy shop, which displays a few of his own toys from his own growing up — WW II soldiers and Jeeps — alongside wind-up steam shovels and a ride-on bull with wheels and other vintage toys; the candy shop, stocked, like the pharmacy, with penny candy — Mint Juleps and Chocolate Babies and Red Hot fireballs (many jars are empty — “I fight the mice in here all winter,” he says). On and on: the barber shop with its Regulator clock, lined-up mugs, and the spittoon in the comer; the doctor’s office with the rolltop desk, leather couch, cane-seated wheelchair, and black bag on the floor.

The dentist’s office is still in the making. There are just a few tools, two chairs, and a mean-looking old treadle drill. “I need more parts here. I’ll stumble onto something,” he says. His wife, Margaret, a wiry, fun-loving woman, has already told me how this happens. “He reads in the paper that so-and-so, a doctor or dentist or whatever, is retiring. Bingo, he’s on the phone!” She laughs.

Over the years she has played the spectator in this, watching from the window as Waine works. She is amused, never troubled, by this accumulation, this little city going up around her.

How did this happen? “It was just a notion,” Waine says. “It seemed like a fun idea. But you see where it went. I’m going right through to the other side of the mountain.”

Indeed. Up a steep footpath, gated by low-hanging branches, Waine continues the tour, to the top of the high hill above his house. If it were cleared of its trees, there would be a million-dollar view of Greenfield and the Pioneer Valley below. But the trees are as thick as ever, except for the two new buildings wedged in. Waine says he just found a place he liked, swept aside the brush, and poured the concrete.

One is a church big enough to hold a hearty Greenfield congregation. It has a white steeple and a floor-to-ceiling, multicolored stained-glass window that his grandmother gave to a church in Hubbardston, Massachusetts, back in the 19th century and which serendipity floated back to Waine. It was one thing that his wife helped him with, holding it steady while he framed it in. Soon he plans to move up here the several dozen fir pews he has stashed under the barn and set them in place.

Next to the church is a schoolhouse, complete with 36 old-fashioned wooden desks screwed to the floor, the seats braced in black cast-iron filigree and blue inkwells in the upper right-hand comers. He’s working on this still, searching out maps and globes and slates. You might think that this would be his first love (he has just retired after 3 1 years of teaching), but it isn’t necessarily his favorite. He seems to enjoy each part of this honeycomb equally. “These are a lot of little loves,” he says of the whole.

He would like to open this someday as a museum. A while back he cleared a place for a small parking lot below his house, but the weeds have grown up in that. Every few years a write-up comes out on his endeavor, and he is quoted as saying that he will open it up for tours “when the project is completed.” Two years more, he usually estimates, whether it is 1968 or 1988.

It isn’t that he isn’t sincere. It’s just that it’s all very involved. For one thing, there are still so many things to do to get ready to have people coming in. The weeds have to come out and curbs have to go in, paths made straight, piles of scrapwood tidied. And then there’s the butcher shop he wants to put in this winter, where the church pews are stored now. Besides, could he handle everything — showing people around and safeguarding all the exhibits at the-same time, just himself? “I don’t know. I was hoping maybe my wife would help.” He pauses, eyes alive with the fun of it. “But I haven’t asked her yet.”

And then there is the matter of permits from the town. A big hurdle. Nowadays there are so many fire codes and rules about this and that. What will he do if he isn’t able to get the proper papers? “Well, then,” he says, trying to appear unperturbed, “we’ll have one heck of a tag sale.”

In 1962 Waine Morse decided to build a make-believe store beside his vegetable garden in Greenfield, MA, to house his burgeoning collection of Americana. He couldn’t stop.

Excerpt from “’The Man Who Build a Town in His Backyard,” Yankee Magazine, December 1989.

It didn’t start out to be like this, a whole village, a toy town that he built, one enterprise at a time. Waine Morse doesn’t know what it started out to be. He remembers that germ of it, a trip that he and his wife, just then his bride, took to a general store behind the Yankee Pedlar inn and restaurant in Holyoke.

Both schoolteachers, they had been married only a couple of months when in February of 1962 they took a trip during school vacation. It was raining, not a great day for an excursion, but when he saw this place, filled as it was with nostalgic reminders of the decades before — the coffee grinder and the penny candy and the old lanterns and the big potbelly stove — it struck him that that was what he would like to have. A store, a place to put reminders of times past.

He was 28 at the time, and he and Margaret had their whole lives together ahead of them. He had already built a small house for them on land that had belonged to his mother since the 1920s. This was just outside of Greenfield, Massachusetts, where the Mohawk Trail begins to climb west. Though it was modest from the outside –shallow-roofed and single-story — the inside gradually accumulated such Victorian treats as paneled walls and parquet floors, velvet couches and ancestral portraits. “It evolved,” he says. That’s the way Waine Morse works.

He started on the store, weekends and nights, building it like an old Cape, and roofing it with slate, taking the design out of his head. When he wasn’t building, he was collecting. “The first thing I got was a coffee grinder for $16,” he says.

Amazing that he can recall, since now the store is stocked to its rafters, floor to ceiling, with washboards, boxes of crackers, butter churns, sacks of flour, coffee cans, biscuit boxes, cakes of Ivory soap, shovels, suspenders, crocks, apple peelers, racks of postcards –an endless inventory of stores past. It might justly be called the collection of a lifetime, except that there is so much else.

Waine Morse is 56 now, his gray hair is thinning, but there is still plenty of bounce in his step. He does not even call this a village. He has no name for this flourishing manifestation of the past, housed in what appears to be a group of sheds, sided in rough pine, the roofs like chicken barns.

It’s what’s inside that matters. Whatever it is, it now surrounds his house, hidden among trees and continuing up the steep hill above. There are weeds high around the foundations and the dirt paths are obscured by the overgrowth. Beside the vegetable garden, an old steam pumper is covered in plastic. Farther down is an old wooden milk wagon, badly in need of buttressing.

Next to the store is the pharmacy, which he built in 1969. “There was a drug store on the way to Sturbridge, in West Warren. I noticed one day that they were going out of business,” he says. He bought the counters and the glass cabinets, as well as the 14-foot-long wall that separated the pharmacist’s work area from his customers — a big, old-fashioned affair that includes mirrors framed by dark-stained wood pillars.

He took it down and brought it back to Greenfield, piece by piece. He reassembled it inside his new building. He worked alone — he did then and does now. From that old drug store and from others, and from items bought at flea markets and yard sales, he began to stock the shelves.

Like the general store, there is not a hairline left for expansion. Crammed into the cases and up on the shelves, Waine has lined up hundreds of packets of herbs (frostwort, blessed thistle, horehound, ignatia) and assortments of salves and medical assists — King’s Kidney Plaster, Grandpa’s Pine Tar Soap, Corn Cure, Tuttle’s Family Elixir, Carter’s Little Pills, Dr. Blue Jay Corn Plasters, Kantleek hot water bottles, Red Raven Splits of “Laxative Water.” There they are, their labels still bright, the wrappers still sealed, full to the top with the old remedies.

Waine Morse has never tried any of them. “I just like to come in here and look,” he says. In the windows sunlight shines through big blue and amber apothecary jars. Other jars and bottles crowd in, shoulder to shoulder.

The store is long since complete. There are two reasons for that. When he was gathering stock for these shelves, in the sixties and seventies, bottles and such could be had for not much. Now the prices are sky-high. “See those two cobalt bottles over there? They’d probably cost $75 apiece now, so hey, I’m done.” It’s not just the money. “I wouldn’t want to buy any more bottles. I would have to build another shelf, and once I hit the ceiling, that’s it.”

After the pharmacy he lost track of the sequence; the years seem to blur. “I’d have to look that up,” he says in answer to questions of when did he put in the doctor’s office and when did he reassemble the tinsmith’s shop. But in truth he doesn’t really have a place to look it up. He’s not absent-minded and heaven knows he is anything but disorganized. It’s just that there is so much. Beyond the pharmacy, there is a big building, more than 100 feet long, with add-ons like shops along a street. And several others, the doors to which Waine Morse opens like surprise packages, moving into the darkness and amid the smell of pine and sawdust until he finds the light, illuminating his creations.

In a comer he has the blacksmith shop, behind a glass wall made of old storm windows. The more-than-man-sized bellows, the anvil as big as a workbench, the collection of tongs on the side of the forge – all of it brought from different sources. Waine didn’t know too much about this kind of work. “For this I got a book that showed how it was done and so I said, ‘Okay, here we go,’ and I looked for one of this and one of that.”

When he read in the paper that Tony Trela, the last blacksmith in Greenfield, had died, he took note. “By the time I got down there, most everything was gone. The tools, that is. But I got what no one else wanted.

I got his chair, his gloves, his boots, and his two hats, one for summer and one for winter. I looked down at the floor. It was covered with metal filings and ashes and coal dust from the forge, old cigar butts and the parings from horses’ hooves.” Waine Morse’s eyes shine in recollection. “The man never swept. NO one else wanted it, but oh, it was beautiful, if you like such things.” Waine swept it up and brought it home. When the time is right, he will carpet the blacksmith’s shop with its majesty.

This is how he came by a lot of what he has. For the buildings, he kept his eye on the paper for old boards and materials. “I never actually took a building down, but I was standing right there while they were being taken down,” he says. And into the back of his father’s pickup would go the doors and the windows, the boards and the beams. Something like half of his buildings come from the old tom-down buildings and barns of Greenfield.

What else he gathered, of course, are the workings of his exhibits. Living as he did in the great industrialized mill valley, as the fifties turned to the sixties and the sixties to the seventies, one mill right after the other shut its doors in Greenfield, in Millers Falls, and most of all in Holyoke.

Most everyone else stood by and watched while this glum transition took hold. Waine Morse went in and got, taking apart the weighty machinery and trucking it back to Greenfield in the same borrowed pickup. “This would all have gone by, otherwise,” he says.

He is talking here not only about things such as the old cracker barrels of which nostalgists are so fond, but of an enormous treadle-operated lathe, a giant hand-cranked drill press, a belt-driven planer that weighs a full ton, an ancient table saw with a wooden bed and a blade reminiscent of scenes from the silent movies.

In the pattern-maker’s shop, bolted to the rafters, Waine has a rope winch that looks capable of reeling in the Queen Mary. Miles of hemp rope are wound to the spool. Waine says the entire unit weighs 1,800 pounds. He should know. “I put it up there piece by piece and it was a pain in the neck, but I bet there isn’t another one like it anywhere.” Probably not. He looks ground him, the tools silent but set like a stage, ready to come to life — all they need are the men and the women and the times past.

In rooms and in separate buildings, he leads me through his version of the past — a dry goods shop (“I’m going to hang curtains in here when the time comes”); the wheelwright’s shop (gently, he runs his fingertips across the spoked wooden wheel, set in its vise, half made); the ice cream parlor with the old marble fountain and soda dispensers (he walks in and straddles one of the stools, puts his elbows on the counter); the toy shop, which displays a few of his own toys from his own growing up — WW II soldiers and Jeeps — alongside wind-up steam shovels and a ride-on bull with wheels and other vintage toys; the candy shop, stocked, like the pharmacy, with penny candy — Mint Juleps and Chocolate Babies and Red Hot fireballs (many jars are empty — “I fight the mice in here all winter,” he says). On and on: the barber shop with its Regulator clock, lined-up mugs, and the spittoon in the comer; the doctor’s office with the rolltop desk, leather couch, cane-seated wheelchair, and black bag on the floor.

The dentist’s office is still in the making. There are just a few tools, two chairs, and a mean-looking old treadle drill. “I need more parts here. I’ll stumble onto something,” he says. His wife, Margaret, a wiry, fun-loving woman, has already told me how this happens. “He reads in the paper that so-and-so, a doctor or dentist or whatever, is retiring. Bingo, he’s on the phone!” She laughs.

Over the years she has played the spectator in this, watching from the window as Waine works. She is amused, never troubled, by this accumulation, this little city going up around her.

How did this happen? “It was just a notion,” Waine says. “It seemed like a fun idea. But you see where it went. I’m going right through to the other side of the mountain.”

Indeed. Up a steep footpath, gated by low-hanging branches, Waine continues the tour, to the top of the high hill above his house. If it were cleared of its trees, there would be a million-dollar view of Greenfield and the Pioneer Valley below. But the trees are as thick as ever, except for the two new buildings wedged in. Waine says he just found a place he liked, swept aside the brush, and poured the concrete.

One is a church big enough to hold a hearty Greenfield congregation. It has a white steeple and a floor-to-ceiling, multicolored stained-glass window that his grandmother gave to a church in Hubbardston, Massachusetts, back in the 19th century and which serendipity floated back to Waine. It was one thing that his wife helped him with, holding it steady while he framed it in. Soon he plans to move up here the several dozen fir pews he has stashed under the barn and set them in place.

Next to the church is a schoolhouse, complete with 36 old-fashioned wooden desks screwed to the floor, the seats braced in black cast-iron filigree and blue inkwells in the upper right-hand comers. He’s working on this still, searching out maps and globes and slates. You might think that this would be his first love (he has just retired after 3 1 years of teaching), but it isn’t necessarily his favorite. He seems to enjoy each part of this honeycomb equally. “These are a lot of little loves,” he says of the whole.

He would like to open this someday as a museum. A while back he cleared a place for a small parking lot below his house, but the weeds have grown up in that. Every few years a write-up comes out on his endeavor, and he is quoted as saying that he will open it up for tours “when the project is completed.” Two years more, he usually estimates, whether it is 1968 or 1988.

It isn’t that he isn’t sincere. It’s just that it’s all very involved. For one thing, there are still so many things to do to get ready to have people coming in. The weeds have to come out and curbs have to go in, paths made straight, piles of scrapwood tidied. And then there’s the butcher shop he wants to put in this winter, where the church pews are stored now. Besides, could he handle everything — showing people around and safeguarding all the exhibits at the-same time, just himself? “I don’t know. I was hoping maybe my wife would help.” He pauses, eyes alive with the fun of it. “But I haven’t asked her yet.”

And then there is the matter of permits from the town. A big hurdle. Nowadays there are so many fire codes and rules about this and that. What will he do if he isn’t able to get the proper papers? “Well, then,” he says, trying to appear unperturbed, “we’ll have one heck of a tag sale.”